Gen Z: Snowflake Celebration or Debate Disaster?

‘Gen Z’. We’ve all heard the term, but what exactly is it, and does it matter? I attended the event ‘Gen Z Debated’ organised by The Policy Institute at King’s College (London) to find out.

The hushed pre-event murmuring bore the voices of those perplexed audience members (including myself) trying to figure out whether they constituted ‘Gen Z’. Luckily, the term was defined presently as describing those born between 1996 and the early 2010s. With narcissistic delight, I realised that the debate was about me.

Professor Linda Woodhead began the evening by presenting a short presentation on her research. Co-author of Gen Z, Explained: The Art of Living in a Digital Age (2021) and with a background in theology, she argued that the true religion of ‘Gen Z’ was, in fact, no religion at all, but rather one’s own voice. The self-inflated puritanical underpinnings of this assertion certainly ring true with a generation molly-coddled by university trigger warnings – such as that issued by the University of Glasgow for James Joyces’ Ulysses (1904) due to its ‘explicit references’ to ‘sexual matters’, just over a century after its initial ban for ‘obscenity’ in 1922

This is a generation – as described by YouTube vlogger Ruby Granger – which celebrates sensitivity, with trigger warnings there to protect. Granger went so far as to argue that we should take pride in being a ‘snowflake’ because it is a recognition that people are vulnerable. Almost as if the talk of ‘trigger warnings’ served as a caution against offense, the ensuing discussion was hardly a ‘debate’. There were some fuzzy areas of disagreement but, in general, these were as electric as a rubber in a wooden box.

Are we, ‘Gen Z’, entirely to blame for our intolerance to the uncomfortable? Fellow ‘Gen Z’-er Khushal Yousafzai claimed not, attributing some of the blame to algorithmic echo chambers. He argued that social media breeds polarisation because clickbait posts generate money, concurrently eroding the emotional intelligence of its users and their ability to debate. I completely agree. Too much time spent on social media creates a false sense of reality, making subsequent exposure to alternative views shock like an ice pool.

Yousafzai advocated freedom of expression to counter this tendency. He suggested that rather than embracing our reputation as ‘snowflakes’, we must learn how to listen by allowing ourselves to be uncomfortable. Rabbi Laura Janner-Klausner also tackled this thorny issue by explaining how ‘trigger warnings’ originated in medical settings for the treatment of PTSD. Now, however, their liberal issue has eroded the authenticity of ‘real’ instances of trauma. In effect, and ironically so, we are losing the tools to express reality through a blanket striving to be ‘authentic’.

The ‘snowflake’ identity celebrated by Granger was therefore tentatively criticised for its threat to human expression. I was somewhat disappointed with Granger due to my appreciation of her aesthetic vlogs, published undoubtedly after many invisible hours of careful planning, filming, and editing. To post high-quality videos with such regularity shows strength of character – the opposite, I would argue, to a ‘snowflake’ personality.

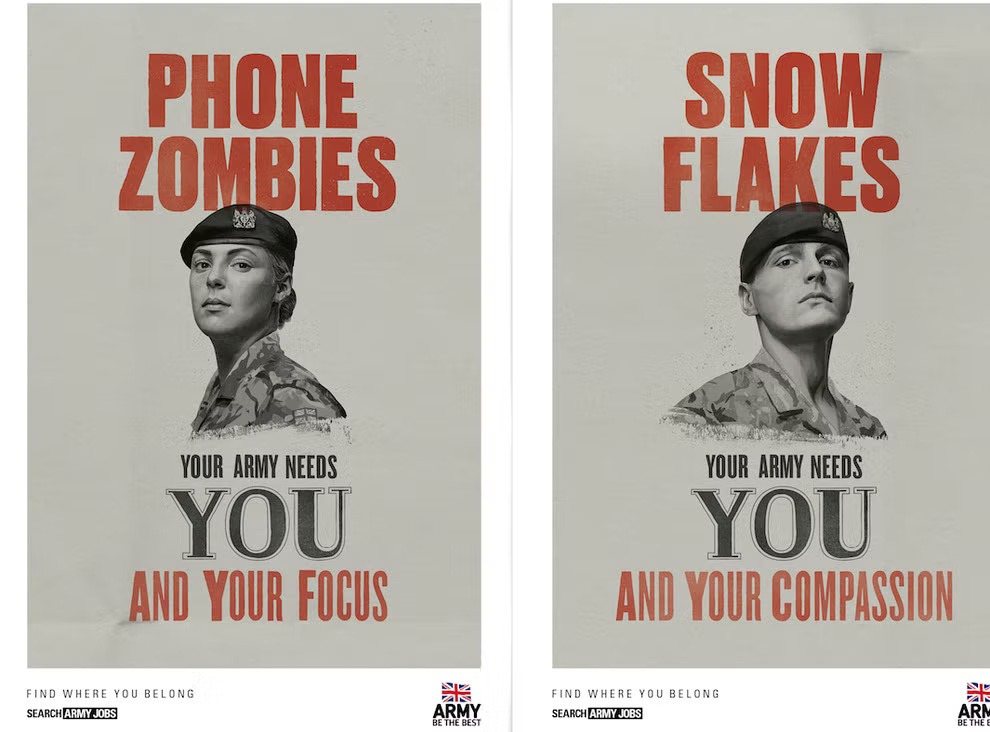

Recruitment posters issued by the British Army (January 2019). It seems that Ruby Granger is not the only one who celebrates the ‘snowflake’.

In fact, this underpins my larger criticism of the softly-softly ‘Gen Z’ generation: why is the ‘victim’ identity lionised above strength as a cardinal virtue? The celebration of vulnerability seems curiously incompatible with the success enjoyed by those who speak the loudest. Rob Henderson’s theory of ‘Luxury Beliefs’ may provide an answer to this conundrum: the idea that the upper classes can espouse ‘ideas and opinions that confer status on the rick at very little cost, while taking a toll on the lower class’.[1] After all, if we are talking about privilege, ‘Gen Z’ is surely guilty. To embrace and be proud of being a snowflake in practice (not just through lip-service) is surely restricted to those within the universities or candyfloss working environments. Such a preoccupation prevents improvement in both mental health and living conditions.

Finally, serving as perfect evidence of an inherent privilege, the panellists discussed the anxiety-inducing amount of choices ‘Gen Z’ face. Undoubtedly, the constant proliferation of choices can be overwhelming, not least since they are in the palm of one’s hand all day, but choices are a luxury (and so are phones!). I personally revel in the idea that, whereas in the past my opportunities as a woman may have been limited, now I can be a mother, not be a mother, be a mother and have a successful career… I can even be a ‘father’, for goodness sake. It is time to either celebrate choices or put that damn phone down. We must shift our perspective.

By the end of the event, I fully understood why I hadn’t known whether I was in ‘Gen Z’ at the start. The reason: I am not preoccupied with identity, nor do I construct divisions between generations due to a personal intolerance. Like Bobby Duffy – the individual behind the debate and author of The Generation Myth: Why When You’re Born Matters Less Than You Think (2021) – I doubt the utility of the term itself. The panellist who most successfully mobilised the ‘Gen Z’ term, however, was Yousafzai. His points were the most grounded in reality (and, consequently, the most ‘controversial’). Only later did I learn that he is brother to Malala Yousafzi, leading me to wonder whether his experience of real trauma had given him a firmer grasp of reality and appreciation of the violence that intolerance can breed.

[1] Rob Henderson, ‘“Luxury beliefs” are the latest status symbol for rich Americans’, New York Post 17 August 2019 [https://nypost.com/2019/08/17/luxury-beliefs-are-the-latest-status-symbol-for-rich-americans/, accessed 4 Feb 2023].